Sanskrt

Sanskrt (संस्कृत, n., od sam "zajedno" i krta "napravljen", doslovno: "sastavljen", "sastavljeni jezik") je klasični jezik koji pripada indoarijskoj grani indoevropskih jezika.[10][11][12] Nastao je u Južnoj Aziji nakon što su se njeni prethodni jezici proširili sa sjeverozapada u kasnom bronzanom dobu.[13][14] Sanskrt je sveti jezik hinduizma, jezik klasične hinduističke filozofije i historijskih tekstova budizma i džainizma. Bio je to jezik veze u drevnoj i srednjovjekovnoj Južnoj Aziji, a nakon prenošenja hinduističke i budističke kulture u Jugoistočnu Aziju, Istočnu Aziju i Srednju Aziju u ranom srednjem vijeku, postao je jezik religije i visoke kulture i političkih elita. u nekim od ovih regiona.[15][16] Kao rezultat toga, Sanskrt je imao trajan uticaj na jezike Južne Azije, Jugoistočne Azije i Istočne Azije, posebno u njihovim formalnim i naučenim rječnicima.[17]

| Sanskrt संस्कृत | |

|---|---|

|

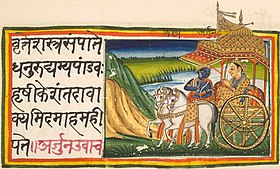

(gore) Ilustrovani sanskritski rukopis iz 19. stoljeća iz Bhagavad Gite,[1] sastavljeno c. 400 – 200 BCE.[2][3] (bottom) Poštanska marka povodom 175. godišnjice trećeg najstarijeg sanskrtskog koledža, osnovanog 1824. | |

| Regije govorenja | Južna Azija, Tibet, Mongolija, Srednja Azija |

| Jezička porodica | |

| Etnički govornici | Nema poznatih govornika sanskrta[4][5][6][7][8][9] |

| Sistem pisanja | Devanagari |

| Službeni status | |

| Služben u | |

| Jezički kod | |

| ISO 639-1 | sa |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | san |

| ISO 639-3 | san |

| Također pogledajte: Jezik | Jezičke porodice | Spisak jezika | |

Sanskrt općenito konotira nekoliko staroindoarijskih jezičnih varijanti.[18][19] Najarhaičniji od njih je Vedski Sanskrt koji se nalazi u Rgvedi, zbirci od 1.028 himni koju su između 1500. godine p. n. e. i 1200. godine p. n. e. sastavila indoarijska plemena koja su migrirala na istok s planina današnjeg sjevernog Afganistana preko sjevernog Pakistana i sjeverozapadne Indije.[20][21] Vedski Sanskrt je stupio u interakciju sa već postojećim drevnim jezicima potkontinenta, upijajući imena novonastalih biljaka i životinja; pored toga, drevni dravidski jezici su uticali na fonologiju i sintaksu Sanskrta.[22] Sanskrt se također uže može odnositi na klasični Sanskrt, rafinirani i standardizirani gramatički oblik koji se pojavio sredinom 1. milenijuma p. n. e. i kodificiran u najsveobuhvatnijoj drevnoj gramatici,[a] Aṣṭādhyāyī ('Osam poglavlja') Pāṇini.[23] Najveći dramaturg na sanskrtu, Kalidāsa, pisao je na klasičnom Sanskrtu, a osnove moderne aritmetike prvi put su opisane na klasičnom sanskrtu.[23]}}[24] Međutim, dva glavna Sanskrtska epa, Mahābhārata i Rāmāyaṇa, sastavljena su u jednoj knjizi. niz registara usmenog pripovijedanja pod nazivom epski Sanskrt koji se koristio u sjevernoj Indiji između 400. godine p. n. e. i 300. godine n. e, i otprilike suvremen sa klasičnim Sanskrtom.[25] U narednim vijekovima, Sanskrt je postao vezan za tradiciju, prestao je da se uči kao prvi jezik i na kraju je prestao da se razvija kao živi jezik.[7]

Himne Rgvede su značajno slične najarhaičnijim pjesmama iranskih i grčkih jezičkih porodica, Gâthâmi starog Avestanskog jezika i Homerove Ilijade.[26] Kako je Rgveda usmeno prenošena metodama pamćenja izuzetne složenosti, strogosti i vjernosti,[27][28] kao jedan tekst bez varijantnog čitanja,[29] njena očuvana arhaična sintaksa i morfologija od vitalnog su značaja u rekonstrukciji jezika zajedničkog pretka Praindoevropskog jezika.[26] Sanskrt nema potvrđeno izvorno pismo: otprilike od početka 1. milenijuma, pisano je raznim bramičkim pismima, a u modernoj eri najčešće na devanagari.[b][30][31]

Status, funkcija i mjesto Sanskrta u indijskom kulturnom naslijeđu prepoznati su njegovim uključivanjem u Ustav indijskih jezika.[32][33] Međutim, uprkos pokušajima oživljavanja,[6][34] u Indiji nema govornika sanskrta.[6][8][35] U svakom od nedavnih desetogodišnjih popisa stanovništva Indije, nekoliko hiljada građana je izjavilo da im je Sanskrt maternji jezik,[c] ali se smatra da brojevi označavaju želju da se uskladi sa prestižem jezika.[4][5][6][36] Sanskrt se učio u tradicionalnim gurukulama od davnina; danas se široko uči na nivou srednjih škola. Najstariji Sanskrtski koledž je Benares Sanskrt College osnovan 1791. a vrijeme vladavine Istočnoindijske kompanije.[37] Sanskrt se i dalje široko koristi kao ceremonijalni i ritualni jezik u hinduističkim i budističkim himnama i pjesmama.

Nekoliko riječi iz Sanskrta (nekad i posredstvom drugih jezika) je našlo svoj put i u bosanski jezik: arijski, avatar, džungla, guru, joga, mandala, mantra, mošus, nirvana, svastika (kukasti krst), tantra.

Historija

urediSanskrt je najstariji indoarijski jezik. Iz Sanskrta su se razvili moderni jezici hindi, urdu, bengali, marathi, kašmiri, punjabi, nepalski jezici i romani (romski jezik). Osim klasičnog Sanskrta postoji i tzv. vedski Sanskrt na kojem su napisane četiri svete hinduske vede.

Struktura

urediSanskrt pripada indijskoj grani indogermanske porodice jezika i time ima zajedničke korijene kao i većina modernih ili klasičnih evropskih jezika. Srodnost se najjednostavnije da pokazati kroz riječi za oca i majku: matr i pitr na Sanskrtu, mater i pater na latinskom, meter (μητηρ) i pater (πατηρ) na starogrčkom. Osim toga se lako da uočiti slična gramatička struktura svih indoevropskih jezika, sa rodom, padežima, vremenima i modusima.

Sanskrt ima osam padeža: nominativ, vokativ, akuzativ, instrumental, dativ, ablativ, genitiv i lokativ. Osim jednine i množine, Sanskrt ima i tzv. dvojinu (kao npr. arapski).

Također pogledajte

urediBilješke

uredi- ^ "All these achievements are dwarfed, though, by the Sanskrit linguistic tradition culminating in the famous grammar by Pāṇini, known as the Aṣṭhādhyāyī. The elegance and comprehensiveness of its architecture have yet to be surpassed by any grammar of any language, and its ingenious methods of stratifying out use and mention, language and metalanguage, and theorem and metatheorem predate key discoveries in western philosophy by millennia."[23]

- ^ "In conclusion, there are strong systemic and paleographic indications that the Brahmi script derived from a Semitic prototype, which, mainly on historical grounds, is most likely to have been Aramaic. However, the details of this problem remain to be worked out, and in any case, it is unlikely that a complete letter-by-letter derivation will ever be possible; for Brahmi may have been more of an adaptation and remodeling, rather than a direct derivation, of the presumptive Semitic prototype, perhaps under the influence of a preexisting Indian tradition of phonetic analysis. However, the Semitic hypothesis is not so strong as to rule out the remote possibility that further discoveries could drastically change the picture. In particular, a relationship of some kind, probably partial or indirect, with the protohistoric Indus Valley script should not be considered entirely out of the question." Salomon 1998, str. 30

- ^ 6,106 Indians in 1981, 49,736 in 1991, 14,135 in 2001, and 24,821 in 2011, have reported Sanskrit to be their mother tongue.[6]

Reference

uredi- ^ Mascaró, Juan (2003). The Bhagavad Gita. Penguin. str. 13 ff. ISBN 978-0-14-044918-1. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 11. 10. 2020.

Bhagavad Gita, intenzivno duhovno djelo, koje čini jedan od kamena temeljaca hinduističke vjere, a također je jedno od remek-djela sanskrtske poezije. (sa zadnje korice)

- ^ Besant, Annie (trans) (1922). "Discourse 1". The Bhagavad-gita; or, The Lord's Song, with text in Devanagari, and English translation. Madras: G. E. Natesan & Co. Arhivirano s originala, 12. 10. 2020. Pristupljeno 10. 10. 2020.

प्रवृत्ते शस्त्रसम्पाते धनुरुद्यम्य पाण्डवः ॥ २० ॥

Then, beholding the sons of Dhritarâshtra standing arrayed, and flight of missiles about to begin, ... the son of Pându, took up his bow,(20)

हृषीकेशं तदा वाक्यमिदमाह महीपते । अर्जुन उवाच । ...॥ २१ ॥

And spake this word to Hrishîkesha, O Lord of Earth: Arjuna said: ... - ^ Radhakrishnan, S. (1948). The Bhagavadgītā: With an introductory essay, Sanskrit text, English translation, and notes. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. str. 86.

... pravyite Sastrasampate

dhanur udyamya pandavah (20)

Then Arjuna, ... looked at the sons of Dhrtarastra drawn up in battle order; and as the flight of missiles (almost) started, he took up his bow.

hystkesam tada vakyam

idam aha mahipate ... (21)

And, O Lord of earth, he spoke this word to Hrsikesha (Krsna): ... - ^ a b McCartney, Patrick (10. 5. 2020), Searching for Sanskrit Speakers in the Indian Census, The Wire, arhivirano s originala, 21. 10. 2020, pristupljeno 24. 11. 2020 Quote: "What this data tells us is that it is very difficult to believe the notion that Jhiri is a "Sanskrit village" where everyone only speaks fluent Sanskrit at a mother tongue level. It is also difficult to accept that the lingua franca of the rural masses is Sanskrit, when most the majority of L1, L2 and L3 Sanskrit tokens are linked to urban areas. The predominance of Sanskrit across the Hindi belt also shows a particular cultural/geographic affection that does not spread equally across the rest of the country. In addition, the clustering with Hindi and English, in the majority of variations possible, also suggests that a certain class element is involved. Essentially, people who identify as speakers of Sanskrit appear to be urban and educated, which possibly implies that the affiliation with Sanskrit is related in some way to at least some sort of Indian, if not, Hindu, nationalism."

- ^ a b McCartney, Patrick (11. 5. 2020), The Myth of 'Sanskrit Villages' and the Realm of Soft Power, The Wire, arhivirano s originala, 24. 1. 2021, pristupljeno 24. 11. 2020 Quote: "Consider the example of this faith-based development narrative that has evolved over the past decade in the state of Uttarakhand. In 2010, Sanskrit became the state's second official language. ... Recently, an updated policy has increased this top-down imposition of language shift, toward Sanskrit. The new policy aims to create a Sanskrit village in every "block" (administrative division) of Uttarakhand. The state of Uttarakhand consists of two divisions, 13 districts, 79 sub-districts and 97 blocks. ... There is hardly a Sanskrit village in even one block in Uttarakhand. The curious thing is that, while 70% of the state's total population live in rural areas, 100pc of the total 246 L1-Sanskrit tokens returned at the 2011 census are from Urban areas. No L1-Sanskrit token comes from any villager who identifies as an L1-Sanskrit speaker in Uttarakhand."

- ^ a b c d e Sreevastan, Ajai (10. 8. 2014). "Where are the Sanskrit speakers?". The Hindu. Chennai. Arhivirano s originala, 24. 12. 2021. Pristupljeno 11. 10. 2020.

Sanskrit is also the only scheduled language that shows wide fluctuations — rising from 6,106 speakers in 1981 to 49,736 in 1991 and then falling dramatically to 14,135 speakers in 2001. "This fluctuation is not necessarily an error of the Census method. People often switch language loyalties depending on the immediate political climate," says Prof. Ganesh Devy of the People's Linguistic Survey of India. ... Because some people "fictitiously" indicate Sanskrit as their mother tongue owing to its high prestige and Constitutional mandate, the Census captures the persisting memory of an ancient language that is no longer anyone's real mother tongue, says B. Mallikarjun of the Center for Classical Language. Hence, the numbers fluctuate in each Census. ... "Sanskrit has influence without presence," says Devy. "We all feel in some corner of the country, Sanskrit is spoken." But even in Karnataka's Mattur, which is often referred to as India's Sanskrit village, hardly a handful indicated Sanskrit as their mother tongue.

- ^ a b Lowe, John J. (2017). Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. str. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-879357-1.

The desire to preserve understanding and knowledge of Sanskrit in the face of ongoing linguistic change drove the development of an indigenous grammatical tradition, which culminated in the composition of the Aṣṭādhyāyī, attributed to the grammarian Pāṇini, no later than the early fourth century BCE. In subsequent centuries, Sanskrit ceased to be learnt as a native language, and eventually ceased to develop as living languages do, becoming increasingly fixed according to the prescriptions of the grammatical tradition.

- ^ a b Ruppel, A. M. (2017). The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit. Cambridge University Press. str. 2. ISBN 978-1-107-08828-3. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 5. 10. 2020.

The study of any ancient (or dead) language is faced with one main challenge: ancient languages have no native speakers who could provide us with examples of simple everyday speech

- ^ Annamalai, E. (2008). "Contexts of multilingualism". u Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (ured.). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. str. 223–. ISBN 978-1-139-46550-2. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 5. 10. 2020.

Some of the migrated languages ... such as Sanskrit and English, remained primarily as a second language, even though their native speakers were lost. Some native languages like the language of the Indus valley were lost with their speakers, while some linguistic communities shifted their language to one or other of the migrants' languages.

- ^ Roger D. Woodard (2008). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. str. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 18. 7. 2018.

The earliest form of this 'oldest' language, Sanskrit, is the one found in the ancient Brahmanic text called the Rigveda, composed c. 1500 BCE. The date makes Sanskrit one of the three earliest of the well-documented languages of the Indo-European family – the other two being Old Hittite and Myceanaean Greek – and, in keeping with its early appearance, Sanskrit has been a cornerstone in the reconstruction of the parent language of the Indo-European family – Proto-Indo-European.

- ^ Bauer, Brigitte L. M. (2017). Nominal Apposition in Indo-European: Its forms and functions, and its evolution in Latin-romance. De Gruyter. str. 90–92. ISBN 978-3-11-046175-6. For detailed comparison of the languages, see pp. 90–126.

- ^ Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (2015). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. str. 26–31. ISBN 978-1-134-92187-4.

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. str. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

Although the collapse of the Indus valley civilization is no longer believed to have been due to an 'Aryan invasion' it is widely thought that, at roughly the same time, or perhaps a few centuries later, new Indo-Aryan-speaking people and influences began to enter the subcontinent from the north-west. Detailed evidence is lacking. Nevertheless, a predecessor of the language that would eventually be called Sanskrit was probably introduced into the north-west sometime between 3,900 and 3,000 years ago. This language was related to one then spoken in eastern Iran; and both of these languages belonged to the Indo-European language family.

- ^ Pinkney, Andrea Marion (2014). "Revealing the Vedas in 'Hinduism': Foundations and issues of interpretation of religions in South Asian Hindu traditions". u Bryan S. Turner; Oscar Salemink (ured.). Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Routledge. str. 38–. ISBN 978-1-317-63646-5.

According to Asko Parpola, the Proto-Indo-Aryan civilization was influenced by two external waves of migrations. The first group originated from the southern Urals (c. 2100 BCE) and mixed with the peoples of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC); this group then proceeded to South Asia, arriving around 1900 BCE. The second wave arrived in northern South Asia around 1750 BCE and mixed with the formerly arrived group, producing the Mitanni Aryans (c. 1500 BCE), a precursor to the peoples of the Ṛgveda. Michael Witzel has assigned an approximate chronology to the strata of Vedic languages, arguing that the language of the Ṛgveda changed through the beginning of the Iron Age in South Asia, which started in the Northwest (Punjab) around 1000 BCE. On the basis of comparative philological evidence, Witzel has suggested a five-stage periodization of Vedic civilization, beginning with the Ṛgveda. On the basis of internal evidence, the Ṛgveda is dated as a late Bronze Age text composed by pastoral migrants with limited settlements, probably between 1350 and 1150 BCE in the Punjab region.

- ^ Michael C. Howard 2012, str. 21

- ^ Pollock, Sheldon (2006). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. str. 14. ISBN 978-0-520-24500-6.

Once Sanskrit emerged from the sacerdotal environment ... it became the sole medium by which ruling elites expressed their power ... Sanskrit probably never functioned as an everyday medium of communication anywhere in the cosmopolis—not in South Asia itself, let alone Southeast Asia ... The work Sanskrit did do ... was directed above all toward articulating a form of ... politics ... as celebration of aesthetic power.

- ^ Burrow 1973, str. 62–64.

- ^ Cardona, George; Luraghi, Silvia (2018). "Sanskrit". u Bernard Comrie (ured.). The World's Major Languages. Taylor & Francis. str. 497–. ISBN 978-1-317-29049-0.

Sanskrit (samskrita- 'adorned, purified') refers to several varieties of Old Indo-Aryan whose most archaic forms are found in Vedic texts: the Rigveda (Ṛgveda), Yajurveda, Sāmveda, Atharvaveda, with various branches.

- ^ Alfred C. Woolner (1986). Introduction to Prakrit. Motilal Banarsidass. str. 3–4. ISBN 978-81-208-0189-9.

If in 'Sanskrit' we include the Vedic language and all dialects of the Old Indian period, then it is true to say that all the Prakrits are derived from Sanskrit. If on the other hand 'Sanskrit' is used more strictly of the Panini-Patanjali language or 'Classical Sanskrit,' then it is untrue to say that any Prakrit is derived from Sanskrit, except that Sauraseni, the Midland Prakrit, is derived from the Old Indian dialect of the Madhyadesa on which Classical Sanskrit was mainly based.

- ^ Lowe, John J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The syntax and semantics of adjectival verb forms. Oxford University Press. str. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-19-100505-3. Arhivirano s originala, 10. 10. 2023. Pristupljeno 13. 10. 2020.

It consists of 1,028 hymns (suktas), highly crafted poetic compositions originally intended for recital during rituals and for the invocation of and communication with the Indo-Aryan gods. Modern scholarly opinion largely agrees that these hymns were composed between around 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE, during the eastward migration of the Indo-Aryan tribes from the mountains of what is today northern Afghanistan across the Punjab into north India.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (2006). "Early Loan Words in Western Central Asia: Indicators of Substrate Populations, Migrations, and Trade Relations". u Victor H. Mair (ured.). Contact And Exchange in the Ancient World. University of Hawaii Press. str. 158–190, 160. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

The Vedas were composed (roughly between 1500-1200 and 500 BCE) in parts of present-day Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and northern India. The oldest text at our disposal is the Rgveda (RV); it is composed in archaic Indo-Aryan (Vedic Sanskrit).

- ^ Shulman, David (2016). Tamil. Harvard University Press. str. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-674-97465-4.

(p. 17) Similarly, we find a large number of other items relating to flora and fauna, grains, pulses, and spices—that is, words that we might expect to have made their way into Sanskrit from the linguistic environment of prehistoric or early-historic India. ... (p. 18) Dravidian certainly influenced Sanskrit phonology and syntax from early on ... (p 19) Vedic Sanskrit was in contact, from very ancient times, with speakers of Dravidian languages, and that the two language families profoundly influenced one another.

- ^ a b c Evans, Nicholas (2009). Dying Words: Endangered languages and what they have to tell us. John Wiley & Sons. str. 27–. ISBN 978-0-631-23305-3.

- ^ Glenn Van Brummelen (2014). "Arithmetic". u Thomas F. Glick; Steven Livesey; Faith Wallis (ured.). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. str. 46–48. ISBN 978-1-135-45932-1. Arhivirano s originala, 10. 10. 2023. Pristupljeno 15. 10. 2020.

The story of the growth of arithmetic from the ancient inheritance to the wealth passed on to the Renaissance is dramatic and passes through several cultures. The most groundbreaking achievement was the evolution of a positional number system, in which the position of a digit within a number determines its value according to powers (usually) of ten (e.g., in 3,285, the "2" refers to hundreds). Its extension to include decimal fractions and the procedures that were made possible by its adoption transformed the abilities of all who calculated, with an effect comparable to the modern invention of the electronic computer. Roughly speaking, this began in India, was transmitted to Islam, and then to the Latin West.

- ^ Lowe, John J. (2017). Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. str. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-879357-1.

The term 'Epic Sanskrit' refers to the language of the two great Sanskrit epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. ... It is likely, therefore, that the epic-like elements found in Vedic sources and the two epics that we have are not directly related, but that both drew on the same source, an oral tradition of storytelling that existed before, throughout, and after the Vedic period.

- ^ a b Lowe, John J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The Syntax and Semantics of Adjectival Verb Forms. Oxford University Press. str. 2–. ISBN 978-0-19-100505-3. Arhivirano s originala, 10. 10. 2023. Pristupljeno 13. 10. 2020.

The importance of the Rigveda for the study of early Indo-Aryan historical linguistics cannot be underestimated. ... its language is ... notably similar in many respects to the most archaic poetic texts of related language families, the Old Avestan Gathas and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, respectively the earliest poetic representatives of the Iranian and Greek language families. Moreover, its manner of preservation, by a system of oral transmission which has preserved the hymns almost without change for 3,000 years, makes it a very trustworthy witness to the Indo-Aryan language of North India in the second millennium BC. Its importance for the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European, particularly in respect of the archaic morphology and syntax it preserves, ... is considerable. Any linguistic investigation into Old Indo-Aryan, Indo-Iranian, or Proto-Indo-European cannot avoid treating the evidence of the Rigveda as of vital importance.

- ^ Staal 1986.

- ^ Filliozat 2004, str. 360–375.

- ^ Filliozat 2004, str. 139.

- ^ Jain, Dhanesh (2007). "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages". u George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (ured.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. str. 47–66, 51. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 12. 10. 2020.

In the history of Indo-Aryan, writing was a later development and its adoption has been slow even in modern times. The first written word comes to us through Asokan inscriptions dating back to the third century BC. Originally, Brahmi was used to write Prakrit (MIA); for Sanskrit (OIA) it was used only four centuries later (Masica 1991: 135). The MIA traditions of Buddhist and Jain texts show greater regard for the written word than the OIA Brahminical tradition, though writing was available to Old Indo-Aryans.

- ^ Salomon, Richard (2007). "The Writing Systems of the Indo-Aryan Languages". u George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (ured.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. str. 67–102. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 12. 10. 2020.

Although in modern usage Sanskrit is most commonly written or printed in Nagari, in theory, it can be represented by virtually any of the main Brahmi-based scripts, and in practice it often is. Thus scripts such as Gujarati, Bangla, and Oriya, as well as the major south Indian scripts, traditionally have been and often still are used in their proper territories for writing Sanskrit. Sanskrit, in other words, is not inherently linked to any particular script, although it does have a special historical connection with Nagari.

- ^ Gazzola, Michele; Wickström, Bengt-Arne (2016). The Economics of Language Policy. MIT Press. str. 469–. ISBN 978-0-262-03470-8.

The Eighth Schedule recognizes India's national languages as including the major regional languages as well as others, such as Sanskrit and Urdu, which contribute to India's cultural heritage. ... The original list of fourteen languages in the Eighth Schedule at the time of the adoption of the Constitution in 1949 has now grown to twenty-two.

- ^ Groff, Cynthia (2017). The Ecology of Language in Multilingual India: Voices of Women and Educators in the Himalayan Foothills. Palgrave Macmillan UK. str. 58–. ISBN 978-1-137-51961-0.

As Mahapatra says: "It is generally believed that the significance for the Eighth Schedule lies in providing a list of languages from which Hindi is directed to draw the appropriate forms, style and expressions for its enrichment" ... Being recognized in the Constitution, however, has had significant relevance for a language's status and functions.

- ^ "Indian village where people speak in Sanskrit". BBC News. 22. 12. 2014. Arhivirano s originala, 5. 4. 2023. Pristupljeno 30. 9. 2020.

- ^ Annamalai, E. (2008). "Contexts of multilingualism". u Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (ured.). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. str. 223–. ISBN 978-1-139-46550-2.

Some of the migrated languages ... such as Sanskrit and English, remained primarily as a second language, even though their native speakers were lost. Some native languages like the language of the Indus valley were lost with their speakers, while some linguistic communities shifted their language to one or other of the migrants' languages.

- ^ Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages – India / States / Union Territories – Sanskrit (PDF), Census of India, 2011, str. 30, arhivirano (PDF) s originala, 9. 10. 2022, pristupljeno 4. 10. 2020

- ^ Seth 2007, str. 171.

Izvori

uredi- Banerji, Sures (1989). A Companion to Sanskrit Literature: Spanning a period of over three thousand years, containing brief accounts of authors, works, characters, technical terms, geographical names, myths, legends, and several appendices. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0063-2.

- Guy L. Beck (2006). Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-421-8.

- Shlomo Biderman (2008). Crossing Horizons: World, Self, and Language in Indian and Western Thought. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51159-9. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- John L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-10260-6.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie (2005). The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1463-6.

- Burrow, Thomas (1973). The Sanskrit Language (3rd, revised izd.). London: Faber & Faber.

- Burrow, Thomas (2001). The Sanskrit Language. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1767-2.

- Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- Cardona, George (1997). Pāṇini - His work and its traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0419-8.

- Cardona, George (2012). Sanskrit Language. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Arhivirano s originala, 16. 10. 2023. Pristupljeno 13. 7. 2018.

- Michael Coulson; Richard Gombrich; James Benson (2011). Complete Sanskrit: A Teach Yourself Guide. Mcgraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-175266-4.

- Harold G. Coward (1990). Karl Potter (ured.). The Philosophy of the Grammarians, in Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. 5. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-81-208-0426-5.

- Peter T. Daniels (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 4. 8. 2018.

- Deshpande, Madhav (2011). "Efforts to vernacularize Sanskrit: Degree of success and failure". u Joshua Fishman; Ofelia Garcia (ured.). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The success-failure continuum in language and ethnic identity efforts. 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1.

- Will Durant (1963). Our oriental heritage. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1567310122. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- Eltschinger, Vincent (2017). "Why Did the Buddhists Adopt Sanskrit?". Open Linguistics. 3 (1). doi:10.1515/opli-2017-0015. ISSN 2300-9969.

- Filliozat, Pierre-Sylvain (2004), "Ancient Sanskrit Mathematics: An Oral Tradition and a Written Literature", u Chemla, Karine; Cohen, Robert S.; Renn, Jürgen; et al. (ured.), History of Science, History of Text (Boston Series in the Philosophy of Science), Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, str. 360–375, doi:10.1007/1-4020-2321-9_7, ISBN 978-1-4020-2320-0

- Robert P. Goldman; Sally J Sutherland Goldman (2002). Devavāṇīpraveśikā: An Introduction to the Sanskrit Language. Center for South Asia Studies, University of California Press. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Goody, Jack (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

- Hanneder, J. (2002). "On 'The Death of Sanskrit'". Indo-Iranian Journal. 45 (4): 293–310. doi:10.1163/000000002124994847. JSTOR 24664154. S2CID 189797805. Arhivirano s originala, 28. 6. 2022. Pristupljeno 28. 6. 2022.

- Hock, Hans Henrich (1983). Kachru, Braj B (ured.). "Language-death phenomena in Sanskrit: grammatical evidence for attrition in contemporary spoken Sanskrit". Studies in the Linguistic Sciences. 13 (2).

- Barbara A. Holdrege (2012). Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-0695-4.

- Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Dhanesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Jamison, Stephanie (2008). Roger D. Woodard (ured.). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 18. 7. 2018.

- Stephanie W. Jamison; Joel P. Brereton (2014). The Rigveda: 3-Volume Set, Volume I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972078-1. Arhivirano s originala, 7. 9. 2023. Pristupljeno 19. 7. 2018.

- Keith, A. Berriedale (1996) [First published 1920]. A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1100-3. Arhivirano s originala, 18. 1. 2024. Pristupljeno 15. 11. 2015.

- Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (2017). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics: An International Handbook. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-026128-8. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- The Fourteenth Dalai Lama (1979). "Sanskrit in Tibetan Literature". The Tibet Journal. 4 (2): 3–5. JSTOR 43299940.

- Donald S. Lopez Jr. (1995). "Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna" (PDF). Numen. Brill Academic. 42 (1): 21–47. doi:10.1163/1568527952598800. hdl:2027.42/43799. JSTOR 3270278. Arhivirano (PDF) s originala, 1. 1. 2011. Pristupljeno 29. 8. 2019.

- Colin P. Masica (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2. Arhivirano s originala, 1. 2. 2023. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Meier-Brügger, Michael (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017433-5. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 15. 11. 2015.

- J. P. Mallory; D. Q. Adams (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928791-8.

- MacDonell, Arthur (2004). A History Of Sanskrit Literature. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-0619-2.

- Sir Monier Monier-Williams (2005). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6. Arhivirano s originala, 11. 1. 2023. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1974). Study of Sanskrit in South-East Asia. Sanskrit College. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Oberlies, Thomas (2003). A Grammar of Epic Sanskrit. Berlin New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014448-2.

- Sheldon Pollock (2009). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26003-0. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2001). "The Death of Sanskrit". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press. 43 (2): 392–426. doi:10.1017/s001041750100353x (neaktivno 1. 11. 2024). JSTOR 2696659. S2CID 35550166.CS1 održavanje: DOI nije aktivan od 2024 (link)

- Louis Renou; Jagbans Kishore Balbir (2004). A history of Sanskrit language. Ajanta. ISBN 978-8-1202-05291. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- A. M. Ruppel (2017). The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08828-3. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3. Arhivirano s originala, 2. 7. 2023. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- Seth, Sanjay (2007). Subject lessons: the Western education of colonial India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4105-5.

- Staal, Frits (1986), The Fidelity of Oral Tradition and the Origins of Science, Mededelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie von Wetenschappen, Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company

- Staal, J. F. (1963). "Sanskrit and Sanskritization". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 22 (3): 261–275. doi:10.2307/2050186. JSTOR 2050186. S2CID 162241490.

- Angus Stevenson; Maurice Waite (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3. Arhivirano s originala, 14. 4. 2023. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- Southworth, Franklin (2004). Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-31777-6.

- Philipp Strazny (2013). Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45522-4. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 18. 7. 2018.

- Umāsvāti, Umaswami (1994). That Which Is. Prevod: Nathmal Tatia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-06-068985-8. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 20. 7. 2018.

- Wayman, Alex (1965). "The Buddhism and the Sanskrit of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 85 (1): 111–115. doi:10.2307/597713. JSTOR 597713.

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 16. 7. 2018.

- Witzel, M. (1997). Inside the texts, beyond the texts: New approaches to the study of the Vedas (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Arhivirano (PDF) s originala, 19. 11. 2021. Pristupljeno 28. 10. 2014.

- Iyengar, V. Gopala (1965). A Concise History of Classical Sanskrit Literature.

- Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43079-8.

- Bloomfield, Maurice; Edgerton, Franklin (1932). Vedic Variants - Part II - Phonetics. Linguistic Society of America.

Dodatna literatura

uredi- Bahadur, P.; Jain, A.; Chauhan, D.S. (2011). "English to Sanskrit Machine Translation". Proceedings of the International Conference & Workshop on Emerging Trends in Technology - ICWET '11. ICWET '11: Proceedings of the International Conference & Workshop on Emerging Trends in Technology. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. str. 641. doi:10.1145/1980022.1980161. ISBN 9781450304498. Arhivirano s originala, 20. 9. 2021. Pristupljeno 20. 9. 2021.

- Bailey, H. W. (1955). "Buddhist Sanskrit". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 87 (1/2): 13–24. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00106975. JSTOR 25581326. S2CID 250346761 Provjerite vrijednost parametra

|s2cid=(pomoć). - Beekes, Robert S.P. (2011). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An introduction (2nd izd.). John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8500-3. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Benware, Wilbur (1974). The Study of Indo-European Vocalism in the 19th Century: From the Beginnings to Whitney and Scherer: A Critical-Historical Account. Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-0894-1.

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1984). Language. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226060675. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 8. 11. 2021.

- Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-74324-8. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Briggs, Rick (15. 3. 1985). "Knowledge Representation in Sanskrit and Artificial Intelligence". AI Magazine. RIACS, NASA Ames Research Center. 6 (1). doi:10.1609/aimag.v6i1.466. S2CID 6836833. Arhivirano s originala, 20. 9. 2021. Pristupljeno 20. 9. 2021.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993). "Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit: The Original Language". Aspects of Buddhist Sanskrit: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Language of Sanskrit Buddhist Texts, 1–5 Oct. 1991. Sarnath. str. 396–423. ISBN 978-81-900149-1-5.

- Chatterji, Suniti Kumar (1957). "Indianism and Sanskrit". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 38 (1/2): 1–33. JSTOR 44082791.

- Clackson, James (18. 10. 2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46734-6.

- Coulson, Michael (1992). Richard Gombrich; James Benson (ured.). Sanskrit : an introduction to the classical language (2nd, revised by Gombrich and Benson izd.). Random House. ISBN 978-0-340-56867-5. OCLC 26550827.

- Filliozat, J. (1955). "Sanskrit as Language of Communication". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 36 (3/4): 179–189. JSTOR 44082954.

- Filliozat, Pierre-Sylvain (2000). The Sanskrit Language: An Overview : History and Structure, Linguistic and Philosophical Representations, Uses and Users. Indica. ISBN 978-81-86569-17-7. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. IV (2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8. Arhivirano s originala, 23. 4. 2023. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, Vjaceslav V. (2010). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Text. Part II: Bibliography, Indexes. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-081503-0. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Gamkrelidze, Thomas V.; Ivanov, V. V. (1990). "The Early History of Indo-European Languages". Scientific American. Nature America. 262 (3): 110–117. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262c.110G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0390-110. JSTOR 24996796.

- Grünendahl, Reinhold (2001). South Indian Scripts in Sanskrit Manuscripts and Prints: Grantha Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Nandinagari. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04504-9. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 13. 7. 2018.

- Huet, Gerard (2005). "A functional toolkit for morphological and phonological processing, application to a Sanskrit tagger". Journal of Functional Programming. Cambridge University Press. 15 (4): 573–614. doi:10.1017/S0956796804005416 (neaktivno 1. 11. 2024). S2CID 483509.CS1 održavanje: DOI nije aktivan od 2024 (link)

- Lehmann, Winfred Philipp (1996). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-13850-5. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S. (2013). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-98595-9. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 13. 1. 2017.

- Kak, Subhash C. (1987). "The Paninian approach to natural language processing". International Journal of Approximate Reasoning. 1 (1): 117–130. doi:10.1016/0888-613X(87)90007-7. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 8. 11. 2021.

- Kessler-Persaud, Anne (2009). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al. (ured.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism: Sacred texts, ritual traditions, arts, concepts. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-17893-9.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- Malhotra, Rajiv (2016). The Battle for Sanskrit: Is Sanskrit Political or Sacred, Oppressive or Liberating, Dead or Alive?. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-9351775386.

- Mallory, J. P. (1992). "In Search of the Indo-Europeans / Language, Archaeology and Myth". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. 67 (1). doi:10.1515/pz-1992-0118. ISSN 1613-0804. S2CID 197841755.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Arhivirano s originala, 19. 2. 2023. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Matilal, Bimal (2015). The word and the world : India's contribution to the study of language. New Delhi, India Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565512-4. OCLC 59319758.

- Maurer, Walter (2001). The Sanskrit language: an introductory grammar and reader. Surrey, England: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1382-0.

- Michael Meier-Brügger (2013). Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-089514-8. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Murray, Tim (2007). Milestones in Archaeology: A Chronological Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-186-1. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Nedi︠a︡lkov, V. P. (2007). Reciprocal constructions. Amsterdam Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. ISBN 978-90-272-2983-0.

- Petersen, Walter (1912). "Vedic, Sanskrit, and Prakrit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 32 (4): 414–428. doi:10.2307/3087594. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 3087594.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. str. 643. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2. Arhivirano s originala, 16. 1. 2023. Pristupljeno 21. 7. 2018.

- Raghavan, V. (1968). "Sanskrit: Flow of Studies". Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 11 (4): 82–87. JSTOR 24157111.

- Raghavan, V. (1965). "Sanskrit". Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 8 (2): 110–115. JSTOR 23329146.

- Renfrew, Colin (1990). Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38675-3. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Sanyal, Ratna; Pappu, Aasish (2008). "Vaakkriti: Sanskrit Tokenizer". Proceedings of the Third International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing: Volume-II. International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (IJCNLP). Arhivirano s originala, 21. 9. 2021. Pristupljeno 20. 9. 2021.

- Shendge, Malati J. (1997). The Language of the Harappans: From Akkadian to Sanskrit. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-325-0. Arhivirano s originala, 29. 3. 2024. Pristupljeno 17. 7. 2018.

- Thieme, Paul (1958). "The Indo-European Language". Scientific American. 199 (4): 63–78. Bibcode:1958SciAm.199d..63T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1058-63. JSTOR 24944793.

- van der Veer, Peter (2008). "Does Sanskrit Knowledge Exist?". Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer. 36 (5/6): 633–641. doi:10.1007/s10781-008-9038-8. JSTOR 23497502. S2CID 170594265.

- Whitney, W.D. (1885). "The Roots of the Sanskrit Language". Transactions of the American Philological Association. JSTOR. 16: 5–29. doi:10.2307/2935779. ISSN 0271-4442. JSTOR 2935779.

Vanjski linkovi

uredi- "INDICORPUS-31". 31 Sanskrt and Dravidian dictionaries for Lingvo.

- Karen Thomson; Jonathan Slocum. "Ancient Sanskrit Online". free online lessons from the "Linguistics Research Center". University of Texas at Austin.

- "Samskrita Bharati". an organisation promoting the usage of Sanskrt

- "Sanskrit Documents". — Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc.

- "Sanskrit texts". Sacred Text Archive.

- "Sanskrit Manuscripts". Cambridge Digital Library.

- "Lexilogos Devanagari Sanskrit Keyboard". for typing Sanskrt in the Devanagari script.

- "Online Sanskrit Dictionary". — sources results from Monier Williams etc.

- "The Sanskrit Grammarian". — dynamic online declension and conjugation tool

- "Online Sanskrit Dictionary". — Sanskrt hypertext dictionary

- "Sanskrit Shlokas collection". — Collection of Sanskrt Shlokas from Various Sanskrt Texts